Metadata

- Author: Lionel Page

- Full Title: The Truth About Happiness

- URL: https://www.optimallyirrational.com/p/the-truth-about-happiness?utm_campaign=post

Highlights

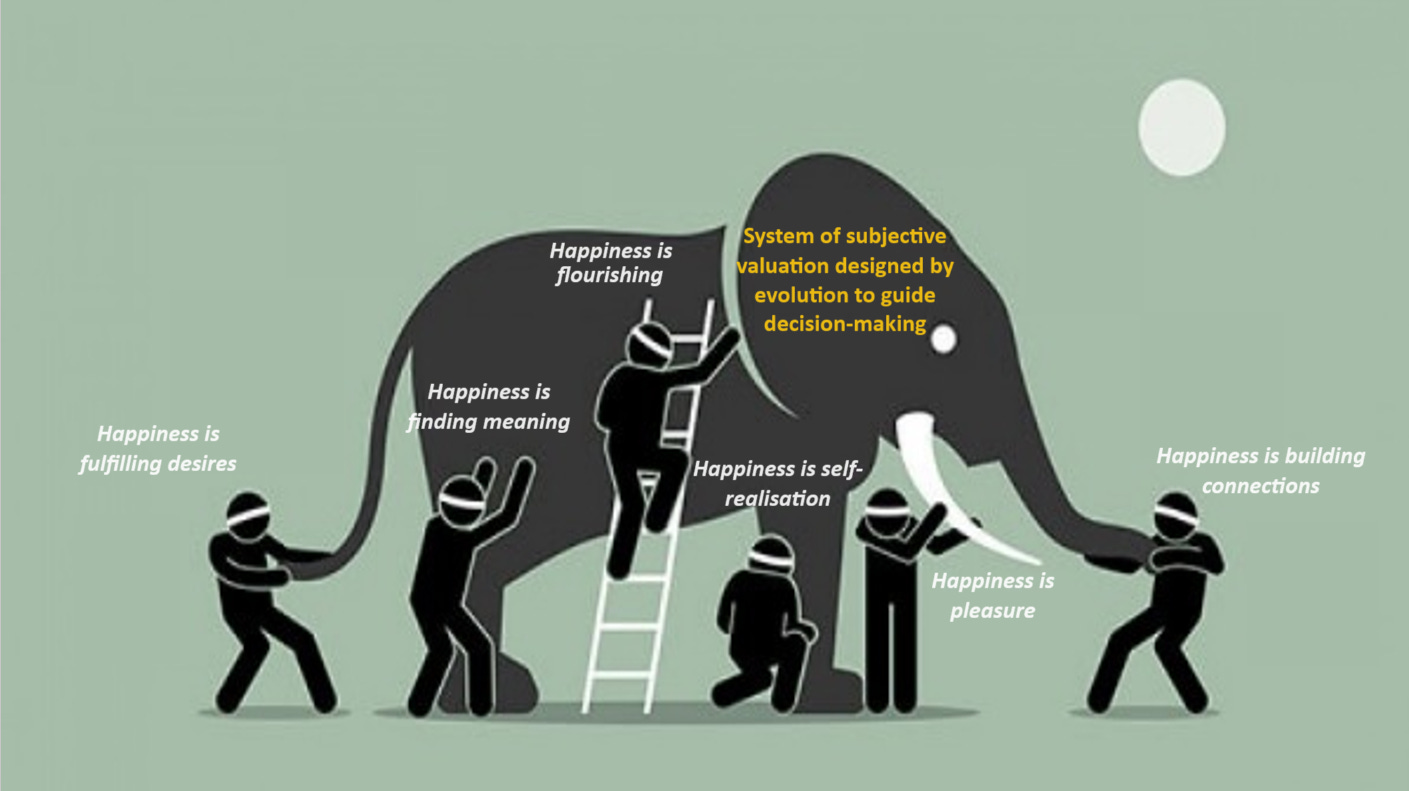

The blind pop psychology books and the happiness elephant (View Highlight)

The blind pop psychology books and the happiness elephant (View Highlight)- In 1973, biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky wrote: “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.” This statement is obviously true; biological life is a product of evolution. From cellular chemistry to human brain cognition, everything is shaped by an incredibly long process of evolutionary selection (View Highlight)

- Dobzhansky’s statement should be complemented with “nothing in human psychology makes sense except in the light of decision-making.” Life is about making decisions: going right or left, fleeing or fighting, eating or avoiding something. An organism’s success or failure at surviving and reproducing depends on its decisions. (View Highlight)

- When an organism chooses between two options, it must be able to identify the best one. When it chooses to take some risk to obtain a possible outcome, it must assess whether the value of this outcome is worth the risk. In short, an organism making decisions benefits from having an internal system of valuation of the options it faces.2 (View Highlight)

- From this perspective, notions like pleasure, subjective satisfaction and well-being are easy to understand. They reflect a system of subjective valuation designed to help us make decisions that are, on average, good for our fitness. This system assigns negative values to harmful things, like touching a hot frying pan, and positive values to beneficial things, like eating energy-rich food.3 (View Highlight)

- Happiness is an affective state that motivates us to engage in actions that are likely to lead to outcomes that would, on average, lead to increases in the likelihood of survival and/or reproduction. - Glenn Geher (View Highlight)

- long-lasting happiness is unachievable. (View Highlight)

- In Die Hard, the evil Gruber states that Alexander the Great wept when he saw that there were no more worlds to conquer.4 The fact that Alexander could be unhappy due to the lack of prospects for further expansion after conquering one of the largest empires in history, strikes us as a tragic aspect of our human condition: habituation. (View Highlight)

Alan Rickman playing the evil Gruber in Die Hard (View Highlight)

Alan Rickman playing the evil Gruber in Die Hard (View Highlight)- The idea of habitation is not new. For instance, Hobbes described it in the Leviathan. Happiness (felicity) cannot be reached in a state of rest, only in a perpetual motion towards greater success:

Continual success in obtaining those things which a man from time to time desireth, that is to say, continual prospering, is that men call felicity; I mean the felicity of this life. For there is no such thing as perpetual tranquillity of mind, while we live here; because life itself is but motion, and can never be without desire, nor without fear, no more than without sense. - Hobbes (1651) (View Highlight)

- we were not designed to be happy. We were designed to strive to be successful. Happiness is not the goal aimed at by evolution. Instead, happiness is just evolution’s trick to guide us towards success in life. (View Highlight)

- If we were to reach long-lasting happiness we would not feel the need to aim for even higher achievements. For that reason, the prospect of long-lasting happiness moves away from us as we move forward. This has been called the hedonic treadmill. (View Highlight)

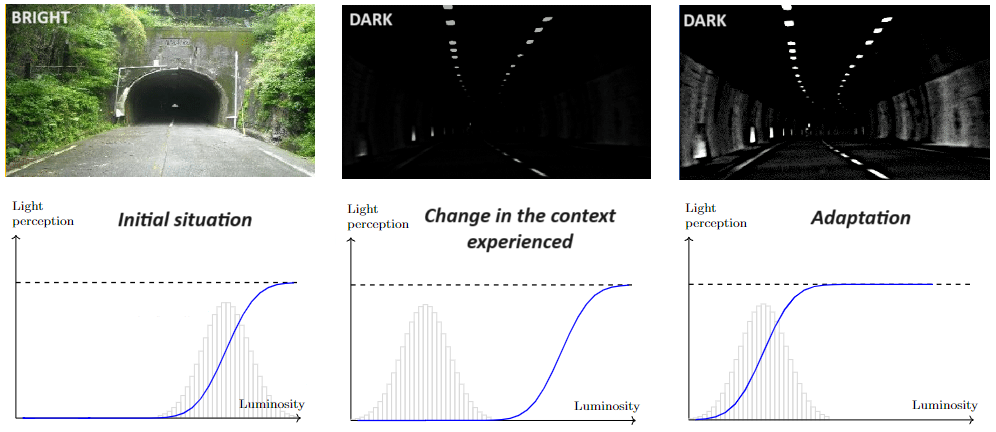

- But you may ask: why does it have to be that way? Why didn’t evolution design us with the ability to simply feel greater and greater happiness when we do better? Why do we habituate to our successes? The answer is that a system of valuation based on variations in success rather than on total success is more efficient in processing information. (View Highlight)

Illustration of the human eye light adaptation. Left : the vision is well-calibrated to perceive the differences of luminosity in the range currently experienced; Centre : the range of luminosity experienced drops, the eye is no longer calibrated, and everything looks similarly dark; Right : the eye adapts to the new environment to be able to discriminate between levels of luminosity in this lower range. (View Highlight)

Illustration of the human eye light adaptation. Left : the vision is well-calibrated to perceive the differences of luminosity in the range currently experienced; Centre : the range of luminosity experienced drops, the eye is no longer calibrated, and everything looks similarly dark; Right : the eye adapts to the new environment to be able to discriminate between levels of luminosity in this lower range. (View Highlight)- All sensory encoding that we know of is reference-dependent. Nowhere in the nervous system are the objective values of consumable rewards encoded. - Glimcher 2011 (View Highlight)

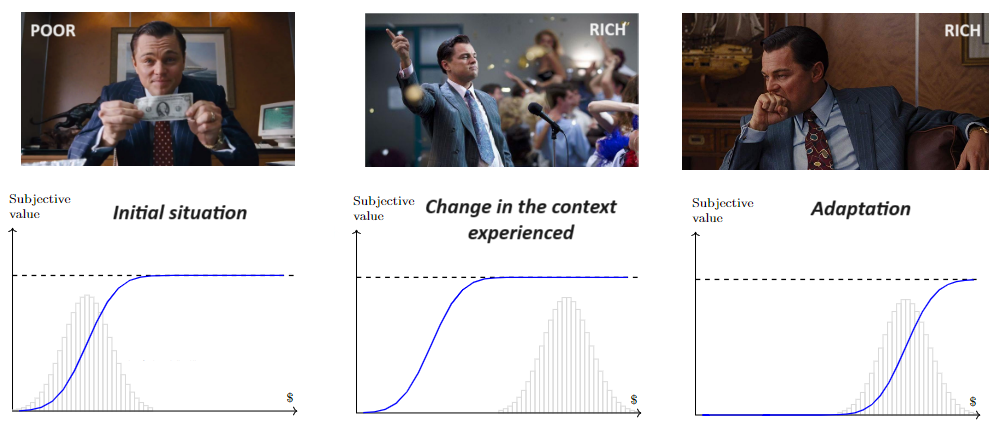

- let’s consider Jordan Belfort’s experience in the movie The Wolf of Wall Street. At the start, Jordan (Leonardo DiCaprio) has relatively modest means. Whenever he makes financial decisions, he must be able to discriminate between good and bad decisions involving small monetary amounts. His subjective perception of variations in wealth (the slope of the blue curve) is then maximal for changes around what he has now (a low level of wealth). (View Highlight)

- After he becomes rich, the range of monetary amounts he faces becomes much higher. Around his new level of wealth, many other levels of wealth feel equally satisfying. It is good for his feelings but not great for his decision-making as he may not care about losing money (e.g. by paying for lavish parties). For Jordan’s decision-making to improve, his subjective satisfaction needs to adapt (habituate) to his new context. Once he habituates, he becomes sensitive to gains or losses around his new wealth level. (View Highlight)

Illustration of subjective satisfaction adaptation : Left : when making decisions where the stakes tend to be low, Jordan is able to carefully discriminate between small variations in wealth; Centre : after becoming rich quickly, everything looks great and Jordan is not able to discriminate between variations of wealth; Right : after experiencing a high level of wealth for some time, Jordan’s subjective satisfaction habituates to it and he is able to perceive (and care about) variations of his level of wealth. (View Highlight)

Illustration of subjective satisfaction adaptation : Left : when making decisions where the stakes tend to be low, Jordan is able to carefully discriminate between small variations in wealth; Centre : after becoming rich quickly, everything looks great and Jordan is not able to discriminate between variations of wealth; Right : after experiencing a high level of wealth for some time, Jordan’s subjective satisfaction habituates to it and he is able to perceive (and care about) variations of his level of wealth. (View Highlight)- As a result, wealthy people do not seem to enjoy the level of happiness we tend to assume we would experience if we had their level of wealth. In a Guardian article, a psychologist for super-wealthy individuals stated:

I’m a therapist to the super-rich: they are as miserable as Succession makes out. Cockrell (2021) (View Highlight)

- The mismatch between the expectations of the experience of success is not restricted to wealth. People’s magazines are replete with stories of celebrities having depression and anxiety. While they typically do not speak candidly about their feelings, when they do it often does not fit our expectations of what we would experience if we had their success. (View Highlight)

- Habituation is a key result of the empirical research on subjective well-being and life satisfaction. People adapt to their changing circumstances—even to life-changing events—and tend to return to a fairly constant level of well-being (Diener, Lucas, and Scollon, 2009).6 (View Highlight)

- It is common to think of happiness as something we could reach if we could get some of the things we want in our lives. This intuition is misleading. Happiness is designed to move away from us as we progressively achieve the things we thought would make us happy. (View Highlight)

- We are designed not for happiness or unhappiness, but to strive for the goals that evolution has built into us. Happiness is a handmaiden to evolution’s purposes here, functioning not so much as an actual reward but as an imaginary goal that gives us direction and purpose. - Nettle (2005) (View Highlight)

- Tags: favorite