In traditional machine learning applications, we have grown accustomed to working with simplistic algorithms. The foundation of the most popular machine learning algorithms is built on the smart combination of estimators known as weak learners. Large Language Models (LLMs) have often been marketed as our path to Artificial General Intelligence, but I see them as the next generation of weak learners.

For a long time, we have relied on combinations of decision trees. Decision trees, a very simplistic form of trainable binary if-else rules, become exceptionally powerful when used in conjunction with many other decision trees. Boosting tree algorithms improve accuracy by having each tree correct the errors of the previous ones, while bagging algorithms achieve precision by averaging the decisions of multiple trees. If you’re unfamiliar with these algorithms, it’s worth noting that Random Forest, XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost have been the workhorses of machine learning practitioners for over a decade, alongside linear and logistic regressions.

In recent weeks, we’ve seen discussions about the plateauing precision gains of LLMs. Influential voices like Ilya Sutskever or François Chollet argue that current AI architectures are nearing their limits in terms of precision, echoing sentiments expressed by Gary Marcus and others for some time. Even LLMs powered by Mixture of Experts, an ensemble approach revisited multiple times by Geoffrey Hinton, struggle to meet the high expectations set by OpenAI and similar companies.

The lack of groundbreaking advances could pose challenges for companies heavily invested in proprietary models, as the promise of true Artificial Intelligence seems to be fading. However, this doesn’t necessarily signal another AI winter in the short term. Instead, the current capabilities of LLMs might be sufficient if we treat them as weak learners and we curate the data effectively.

Ensembling Weak Agents

The real disruption of this generation of AI architectures is how they’ve lowered the entry barriers for applying machine learning to natural language and even images. While some venture capitalists dream of AI models achieving near-human capabilities, practitioners in private companies are more concerned with leveraging current technology to automate mundane, low-risk, time-consuming tasks. In this regard, we already have experience using simplistic models effectively, as demonstrated by tree-based algorithms.

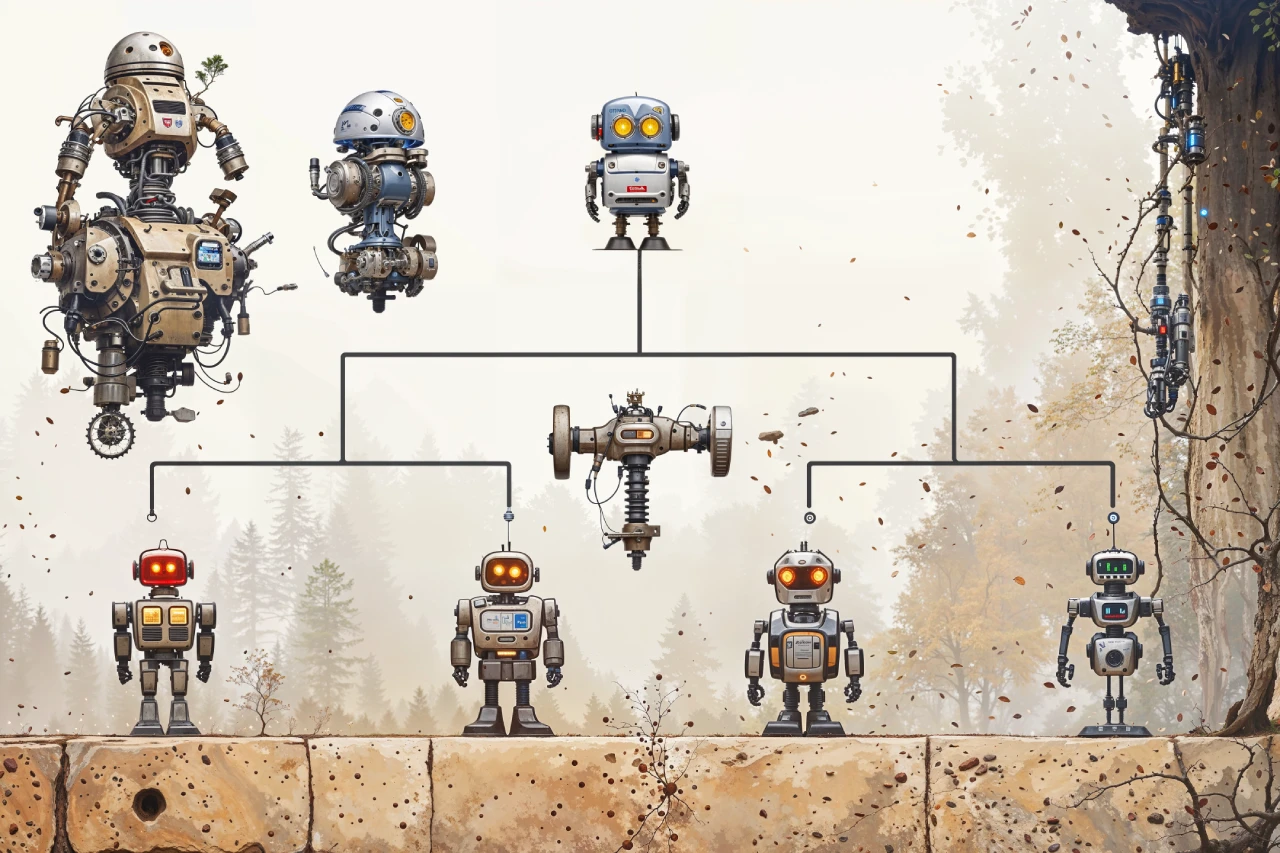

Multi-agent systems could be highly beneficial for this purpose. Let’s define an agent as an LLM with a specific goal, background, and tools. A multi-agent architecture is a collection of LLMs that can act sequentially, in parallel, or hierarchically.

For instance, consider a typical customer support project. Many of us have prototyped solutions using Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), but these solutions often aren’t publicly deployed due to issues like hallucinations. The hypothesis I am posing here is that we might not need an AGI algorithm to solve such tasks; instead, a combination of weak agents powered by LLMs could be good enough.

Here’s how it could work: When a customer submits a question, a database engine retrieves related information. This context could then be passed to a single agent or distributed in parallel among multiple agents, each with its own backend LLM, prompt, and role. Some agents might evaluate whether the retrieved information is sufficient and, if not, rephrase the query to improve retrieval results.

Similarly, during the generation step, multiple agent writers could collaborate, with the best response selected or responses combined. The architecture of such a “swarm of agents” could be tailored creatively, much like how a manager assigns tasks to team members when tackling a project and judge if they are performing as expected. The difference is that we may be bold and aim for teams of 10s or 100s of agents combining their decisions, such as the 100s of trees we usually use in ML tree-based algorithms.

Efficiency and Ease of Use

Is the combination of agents based on LLMs efficient? Not particularly. This parallels machine learning algorithms, where linear models are often the most efficient solution considering the trade-off between complexity and accuracy. Linear variants like Generalized Additive Models (GAMs) can be incredibly powerful but they require much greater expertise. Data scientists frequently rely on tree-based algorithms because, despite their inefficiency, they are easier to train and handle real-world data or model misspecifications effectively. The labor costs associated with creating a good linear model often outweigh the computational costs of using more complex algorithms.

Similarly, LLMs and Large Vision Models (LVMs) have significantly lowered the barriers to solving many NLP and Computer Vision problems that previously required traditional techniques or non-transformer deep learning models. The combination of LLMs, even smaller variants, may be another example of overkill usage. Yet, as history shows, we tend to adopt techniques that are easier to apply, even if they are not the most efficient.

Currently, the high computational costs of combining different LLMs limit such applications. However, with ongoing investments in infrastructure and the historical trend of decreasing computational costs, we can expect the cost of runing inference on multi-agent architectures to drop rapidly. If this happens, we will likely see a shift toward more compute-intensive algorithms, even at the expense of classical solutions that require greater expertise to implement.

In the end, we may not need ultra-powerful LLMs. Binary trees are a simple tool but have proven to be incredibly effective when combined intelligently. Perhaps the future lies in turning weak LLMs into strong learners by ensembling them in a bagging or boosting fashion.

Are these agents truly intelligent? No. Does that matter? Not entirely. Have we ever considered binary trees to be “smart”? Probably not, because we don’t interact with them conversationally. Yet they’ve always been part of what we call Artificial Intelligence. Don’t be surprised if, in the coming years, we see a surge in pooling, averaging, or ensembling agents powered by “dumb” LLMs.